"Hamel's Trip to Joseon"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| 16번째 줄: | 16번째 줄: | ||

<gallery mode=packed heights=220px> | <gallery mode=packed heights=220px> | ||

| + | 파일:4-5.하멜기념비_하멜기념비.jpg| Hamel Memorial Monument (Seogwipo, Jeju) / Courtesy of the Korea Tourism Organization | ||

| + | 파일:4-5.하멜상선 모형_Hamei Ship Exhibition (2).jpg|Hamel Ship Exhibition (Seogwipo, Jeju) / Courtesy of the Korea Tourism Organization (Kim Ji-ho) | ||

| + | 파일:4-5.하멜상선 모형_Hamei Ship Exhibition.jpg|Hamel Ship Exhibition (Seogwipo, Jeju) / Courtesy of the Korea Tourism Organization (Kim Ji-ho) | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

<gallery mode=packed heights=220px> | <gallery mode=packed heights=220px> | ||

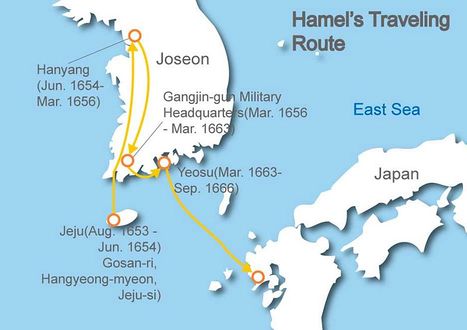

| + | File:040(E).jpg|Hamel's Travel Route | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

=='''Related Articles'''== | =='''Related Articles'''== | ||

| − | |||

=='''References'''== | =='''References'''== | ||

2017년 11월 25일 (토) 11:38 판

It was during the reign of Joseon’s King Hyojong when the damaged Dutch commercial vessel De Sperwer (“The Sparrowhawk”), sailing from Formosa to Japan drifted to Jeju Island at the end of July in 1653. The sailors were arrested, and were held in Joseon for 13 years and 28 days. Eight of them escaped and returned to the Netherlands via Japan. One of the survivors, Hendrick Hamel, published a book documenting his life in Joseon – Hamel's Journal and a Description of the Kingdom of Korea, 1653-1666. Only 36 crew members survived the storms, and 20 more died during their stay in Korea. Only 16 members eventually returned to the Netherlands.

Another Dutch sailor named Jan Janse de Weltevree (K: Park Yeon) had also settled in Joseon in 1628, and served as a translator. He stayed with them for three more years, and taught them Joseon’s language and customs. The Joseon government hoped Hamel and the crew could be as knowledgeable as Weltevree, but they were mostly boys in late teens when they arrived in Joseon, and only could do simple chores.

For almost next 14 years, Hamel and the crew members suffered from forced labor, imprisonment, corporal punishment, exile, and other difficulties. When neglected by local official in charge, they had to resort to begging to survive. During these years, they encountered people from all classes, and were able to observe various traditions and customs of Joseon; this later became the foundation for Hamel’s Journal.

Prior to the escape, 16 survivors were held in southwest Korea by the sea. They were able to find a small boat and navigate to nearby islands to find food and also examine the tides and wind directions. In September 1666, other eight crew members successfully escaped. They returned to Amsterdam in July 1668 via Nagasaki, Japan. The remaining eight crew members were released two years later, and returned to the Netherlands as well.

Hamel requested his back salary for the past 13 years, and submitted his Journal as evidence of drifting at sea. In 1668, his book was published by three different publishers in Amsterdam simultaneously. It was later published in France, United Kingdom, Germany, and other European countries. The first part of the book describes the travel to Korea, followed by the second part on Joseon’s geography, politics, military, customs, education, and other aspects. While this part contains a lot of misinformation, the book presents a lot of useful information on Joseon’s society in the 17th century, including people’s daily lives.

This book is the first record of Korea introducing Joseon to the West, and is historically extremely valuable in that it examines Joseon in an objective manner. Hamel’s Journal also helps researchers today learn about the Korean language in the 17th century. The pronunciations in the book explain how some characters that are no longer used today were pronounced. In October 1980, the Korean and Dutch governments erected a monument to commemorate Hamel in City of Seogwipo, Jeju, near the presumed wreck site.