"Decree Appointing Yi Sunsin to Concurrently Hold the Position of Naval Commander of the Three Provinces of Ch'ungch'ŏng, Chŏlla, and Kyŏngsang"의 두 판 사이의 차이

| (같은 사용자에 의한 하나의 중간 편집이 숨겨짐) | |||

| 8번째 줄: | 8번째 줄: | ||

|Author = [[King Sŏnjo]] | |Author = [[King Sŏnjo]] | ||

|Year = [[1597]] | |Year = [[1597]] | ||

| − | |Key Concepts= Imjin War, Yi Sunsin, Japan-Korea Relations | + | |Key Concepts= [[임진왜란|Imjin War]], Yi Sunsin, Japan-Korea Relations |

|Translator = [[2016 Hanmun Workshop | Participants of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program]] | |Translator = [[2016 Hanmun Workshop | Participants of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program]] | ||

|Editor = [http://scholar.harvard.edu/kang Hyeok Hweon Kang], [[Lethbridge Orion|Orion Lethbridge]] | |Editor = [http://scholar.harvard.edu/kang Hyeok Hweon Kang], [[Lethbridge Orion|Orion Lethbridge]] | ||

2017년 3월 14일 (화) 10:21 기준 최신판

| Primary Source Document | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | |

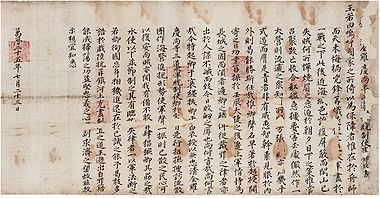

| English | Decree Appointing Yi Sunsin to Concurrently Hold the Position of Naval Commander of the Three Provinces of Ch'ungch'ŏng, Chŏlla, and Kyŏngsang |

| Chinese | 敎 兼忠淸全羅慶尙等三道水軍統制使 李舜臣書 |

| Korean | 교 겸충청전라경상등삼도수군통제사 이순신서 |

| Document Details | |

| Genre | Royal Documents |

| Type | Decree |

| Author(s) | King Sŏnjo |

| Year | 1597 |

| Key Concepts | Imjin War, Yi Sunsin, Japan-Korea Relations |

| Translation Info | |

| Translator(s) | Participants of 2016 Jangseogak Hanmun Workshop Program |

| Editor(s) | Hyeok Hweon Kang, Orion Lethbridge |

| Year | 2016 |

Introduction

- View together with Instructions for the Secret Tally.

In 1592, a Japanese invasion of Korea set off the First Great East Asian War.[1] For seven years, this war engulfed the Korean peninsula and its waters with international conflict of rare precedent in world history. Engaging three belligerent states – Ming China, Chosŏn Korea, and a newly unified Japan – the war featured colossal armies, mass-produced firearms and foreign mercenaries. Fighting in this war was Yi Sunsin (李舜臣, 1545-1598), a famed military commander of Chosŏn Korea (1392-1910) who led tide-turning victories against the Japanese navy.

At the outset of the war, the Chosŏn military was woefully unprepared, atrophied by long peace, factional strife and military neglect. On the other hand, forged in a century of war and armed with muskets, Japanese invaders blasted through Korean defenses and took the capital in less than three weeks. Among various factors that enabled the reversal of Japanese forces such as the advent of righteous armies and Ming aid troops, none was more crucial than the role of Yi Sunsin’s navy. His victories at sea helped thwart Japanese advances and unsettled the enemy’s military logistics by blocking their supply routes. Yi often led victories against the odds, enforcing strict military discipline, strategizing with utmost circumspection, and famously deploying turtle ships, an iron-clad with superior firepower and ramming capacity.

Despite his distinguished service, Yi was nevertheless framed and relieved of military command in 1597. At the time, misinformation by a Japanese double agent led King Sŏnjo (宣祖; r. 1567-1608) to order a risky ambush, and Yi was reprimanded and arrested when he hesitated to act on royal order. He was thus imprisoned and demoted to a rank-and-file soldier (白衣從軍). Soon thereafter, on 15 July 1597, the Japanese availed of Yi’s absence and launched a second invasion. At the Battle of Ch’ilch’ŏnnyang (漆川梁), the entire Chosŏn navy was nearly exterminated, save for a small detachment of twelve warships. On 23 July 1597, about a week after the crushing defeat, King Sŏnjo bestowed the following letter of instruction to Yi to remind him of the precarious military situation and reinstate him as regional naval commander (三道水軍統制使),[2] the position of supreme commander for the Chosŏn navy.

Attached to the letter was also a royal instruction about the secret tally (密符諭書). Customarily, the tally was provided to provincial governors and military commanders who were entrusted with the armed forces of a particular region. The secret tally system was designed to enable the receiving official to dispatch troops swiftly and surreptitiously in case of urgent crises such as rebellions and invasions. As opposed to the more common “troop mobilizing tally” (發兵符), the secret tally was provided only to high-ranking officials and together with a royal instruction. According to procedure, the tally is broken in half, and the king would keep the left half whereas the official would receive the right half. In case of an emergency decree, a royal instruction would be sent down with the king’s tally, with which the official would match his half to confirm its authenticity.

Primary Source Text

| English | Classical Chinese |

|---|---|

| The king says thus: Alas! The only thing that the dynasty can depend on to protect it is the navy. But heaven has not yet relented in bringing calamity [to the dynasty]. The [enemy’s] vicious spears blazed again, and overcame the great navy of the three provinces in just one battle. After this, who will reinforce the defenses in the coastal regions? Hansan Island is already lost; what does the enemy have to fear?[3]

Facing this immediate crisis, hard-pressed day and night, the [only] strategy before us is to summon the scattered [forces] together, assemble the warships, and quickly retake a position of strategic importance, quietly consolidating one major stronghold. Then, the fleeing masses would know where they can return to, and the encroaching enemy might be stopped. If the one who bears the responsibility [for this task] does not have authority, benevolence, intelligence, and fortitude, such that he will be obeyed by all, then how could he bear this task? My minister, you gained a splendid reputation even before the day you assumed high military office, and since your meritorious exploits in the great victory of the Imjin year [1592], the military situation on the frontiers has depended on you for being as firm as the Great Wall. But in recent times, due to the schemes of another,[4] you have been removed from office and made to bear the punishment of law. [The effects of this] have extended to the humiliation of today’s defeat. What can I say? What can I say? Now, I am specifically raising you from mourning garb, and elevating you from commoner status.[5] I reinstate you to concurrently hold the position of Naval Commander of the Three Provinces of Ch'ungch'ŏng, Chŏlla, and Kyŏngsang. From today, first rally and placate [the troops], search out those who have scattered, and unite and build up the naval forces, so as to advance and take control of the situation. If you make the army rise as one, the minds of the people, which have become scattered, will be at ease once more, and the enemy, hearing that we are fully equipped, will not dare to indulge in wanton destruction again. You must attend to this. From the naval commanders and below, all must be disciplined. Anyone who breaks with military regulation should be punished, uniformly and in accordance with the law. You have already proven your selfless sacrifice for the state and [ability to] read the flow of battle. How could I dare presume to instruct you on this? Indeed, as when Lu Kang rebuilt the defenses on the river in order to fully execute his duty,[6] and Wang Xun emerged from the criminal registers to successfully cleanse [the realm],[7] a loyal and righteous heart can fulfil [a sovereign’s wish] for [the] salvation [of the people]. For this reason I make the appointment. Be mindful of it. On the 23rd day of the 9th month in the 25thyear of the reign of Wanli |

王若曰嗚呼 國家之所倚以爲保障者 惟在於舟師 而天未悔禍 兇鋒再熾 遂使三道大軍 盡於一戰之下 此後近海城邑 誰復屛蔽 而閑山已失 賊何所憚 燒眉之急 迫於朝夕 目下之策 惟當召聚散亡 收合船艦 急據要害去處 儼然作一大營 則流逋之衆 知有所歸 方張之賊 亦庶幾乎式遏 而膺是責者 非有威惠智幹素見服於內外 則曷能勝斯任哉 惟卿聲名早著於超授閫寄之日 功業再振於壬辰大捷之後 邊上軍情 恃爲長城之固 而頃者遆卿之職 俾從戴罪之律者亦出於人謀不臧 而致今日敗衂之辱也尙何言哉 尙何言哉 今特起卿于墨衰 拔卿于白衣 授以兼忠淸全羅慶尙等三道水軍統制使 卿於至之日 先行招撫 搜訪流散 團作海營 進扼形勢 使軍聲一振 則已散之民心 可以復安 而賊亦聞我有備 不敢再肆猖獗 卿其勖之哉 水使以下並節制之 其有臨機失律者 一以軍法斷之 若卿殉國忘身 相機進退 在於已試之能 予曷敢多誥 於戲 陸抗再鎭河上 克盡制置之道 王遜出自罪籍 能成掃蕩之功 益堅忠義之心 庶副求濟之望 故玆敎示 想宜知悉 萬曆二十五年七月二十三日 |

Discussion Questions

- View together with Instructions for the Secret Tally.

- How does King Sŏnjo present his own role in Yi Sunsin’s demotion and reinstatement? What wrong was done to Yi in the past per this instruction? What can you surmise about the relationship between Sŏnjo and Yi Sunsin? Is the king apologetic?

- Under what circumstances did the king write this instruction to Yi Sunsin? What do the documents above tell us about the military situation in 1597 at the outset of a second Japanese invasion?

- When the king laments the loss of Hansan Island, which battle is he referring to? Why was this battle so important?

- Is the king offering Yi Sunsin a carrot or a stick?

Further Readings

- Swope, Kenneth M. A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592-1598. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

- Yi Sunsin (1545-1598). Nanjung ilgi: war diary of Admiral Yi Sun-sin. Translated by Ha Tae-hung; edited by Sohn Pow-key. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University Press, 1977.

- Yu Sŏngnyong (1542–1607). The Book of Corrections: Reflections on the National Crisis during the Japanese Invasion of Korea, 1592–1598. Translated by Choi Byonghyon. Berkeley Calif.: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 2002.

References

- ↑ There are various names for this war. In English scholarship, it has been commonly referred to as the Imjin War, Japanese invasions of Korea, Hideyoshi’s invasions or the First Great East Asian War.

- ↑ As shown in the documents below, the literal translation of this title is, “Naval Commander of the Three Provinces of Ch'ungch'ŏng, Chŏlla, and Kyŏngsang.” The regional navy commander served as the supreme commander for the entire Chosŏn navy, and would often be concurrently appointed as navy commander for one of the three provincial navies. The navy commanders of the two other provinces were under the command of the regional navy commander.

- ↑ Hansan Island閑山, on the southern end of the Korean peninsula, was a location of great tactical importance. It was the place where Yi Sunshin led one of his most renowned naval victories in 1592. However, after Yi was framed and relieved of command, Hansan Island fell to Japanese hands after the Battle of Ch’ilch’ŏnnyang (漆川梁), when the entire Chosŏn navy was nearly exterminated, save for a small detachment of twelve warships.

- ↑ This likely refers to Won Kyun (元均, 1540-1597), a Chosŏn navy commander who had personal conflicts with Yi Sunshin and contributed to Yi’s removal from office. By the time of the Battle of Ch’ilch’ŏnnyang, Won Kyun had replaced Yi as the regional naval commander.

- ↑ Yi Sunshin’s mother had died earlier that year, and was in mourning. Typically, while in mourning one could not hold office. ‘Commoner status’ is literally written as ‘white robes’ 白衣, which refers to a demoted official.

- ↑ Lu Kang陸抗 (226-274 C.E) was a famed military general who served the state of Wu and is celebrated for his good judgement, upright conduct, and intelligent military tactics in defense of Wu, though he also opposed unnecessary military aggression on the part of his ruler Sun Hao 孫皓 (Sanguozhi vol. 58).

- ↑ There are multiple historical figures named Wang Xun 王遜, but they do not appear to match the description of someone ‘rising from the criminal register’ in this text. There was a Wang Xun 王遜 (d. 325 C.E) known for his great accomplishments who lived during the Jin dynasty (Jinshu vol. 81). He does not seem to have any connection to criminal behavior. (His biography in the Jinshu is immediately followed by that of a military official of the Jin dynasty, Cai Bao 蔡豹, who appears to have had a more colorful life experience. Is this possibly the confusion?) Wang Jian 王儉 also had a younger brother of the name Xun, who was criminalized, and regarded as far from the conduct of his elder brother. There is also the possibility that the decree refers to Wang Xun, governor of Henan during the reign of Emperor Wu/Sima Yan, who is said to have strictly enforced prohibitions about recruiting clients, which may relate to the mention of ‘registers’ here.